The word ‘polyglot’ has its origins in Greek meaning the ‘ability to speak many languages’.

Having reviewed the literature and theories on polyglottism, it seems to me that an intersubjective examination is needed on where the thresholds should be with the polyglot community.

So to what level should I speak a language in order for it to count?

Obviously speaking a language should be more than simply being able to order in a restaurant. Using the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR), B2 level is approximately the minimum to be able to say that you ‘speak’ a language. The CEFR describes B2 level as an “independent user” with the following competences in reading, listening, speaking and writing:

1. Can understand the main ideas of complex text on both concrete and abstract topics, including technical discussions in his/her field of specialization.

2. Can interact with a degree of fluency and spontaneity that makes regular interaction with native speakers quite possible without strain for either party.

3. Can produce clear, detailed text on a wide range of subjects and explain a viewpoint on a topical issue giving the advantages and disadvantages of various options.

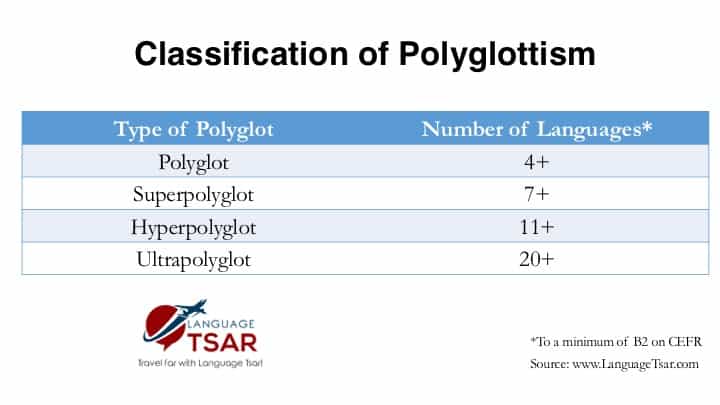

This is still clearly a bit away from native-like fluency but competent enough for effective communication in almost all situations. All languages must be maintained at least this level in order to claim to ‘speak’ them. Passing the level once for the purposes of an exam is not sufficient. B2 is the very minimum. There were solid arguments made during the intersubjective debate that C1 “proficiency” would be a better benchmark of “fluency”. However, as a polyglot expands his repertoire of languages, the time that can be spent with each language is reduced making permanently maintaining such a high level more difficult. Thus, B2 level without any preparation is a more accurate minimum. With 10+ languages I would place myself in the ‘superpolyglot’ category

How diverse should the languages be?

Languages are organized into families and then into family branches, e.g. the Indo-European language family has a Germanic branch of which English, German and Dutch are members. Within family branches familiarity with one language normally makes it a lot easier to understand and learn the other languages within the same family branch. Therefore, within polyglot categories there should be a minimum amount of linguistic family variety, i.e. that not all languages are from one or two family branches.

Dialects are not counted as they are not linguistically diverse enough to constitute a new language nor are non-verbal languages included for the purposes of the classification as the means of communication differs significantly from verbal languages. With respect to dialects, it is sometimes not easy for linguistic or political reasons to say what is a dialect or a separate language (Bosnian v Croatian v Montenegrin v Serbian, for example) but in most cases it is clear.

So how many languages does one have to speak to become a polyglot?

As the root of the word only means ‘many’ then one could argue that just by being multilingual, one is a ‘polyglot’. However, in popular imagination ‘polyglot’ has come to mean something more than just a few. Being a ‘polyglot’ can certainly arise from living in a country where just by living there obliges you to be multilingual, e.g., Luxembourg, India and parts of Africa, in particular. For this reason, I would say that one should speak a minimum of 4 languages in order to describe oneself as a ‘polyglot’.

So what do we call people who go well beyond 4 languages?

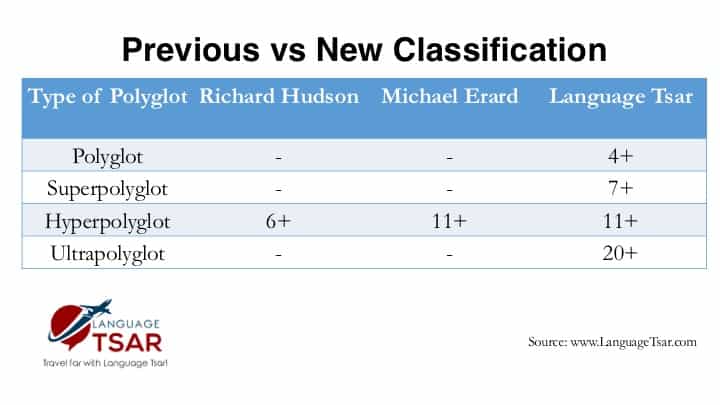

In his book, ‘Babel no more’, Michael Erard argues that a ‘hyperpolyglot’ is someone who speaks 11 or more languages because he thought that’s where language learning gets ‘interesting’. Previously, Richard Hudson had argued that 6 or more languages made someone a ‘hyperpolyglot’ because there are societies where it is normal for people to speak 5 languages (as per the examples cited above). However, if we take the case of Luxembourg, a child of immigrants, say from Portugal, should grow up without much additional effort to speak Luxembourgish, Portuguese, French, German, Dutch and English. Therefore, a category that I will call ‘superpolyglot’ should be these 6 languages plus one, i.e. 7 or more. Also the languages should come from a minimum of 2 language family branches. Renowned superpolyglots who come to mind are Steve Kaufmann, Benny Lewis, Susanna Zaraysky, Stu Jay Raj and Olly Richards.

The phenomenon that Erard has observed as ‘hyperpolyglottism’ cannot really be the highest level within the language language world. While 11+ is indeed an interesting benchmark, it is too limiting when one considers the great polyglots from history who may have spoken up to 50 languages, e.g. Mezzofanti or Emil Krebs. Still, 11 languages to a minimum of a B2 level is an exceptional feat to reach as a language learner. The languages should come from a minimum of 3 language family branches in the ‘hyperployglot’ category. Examples of such ‘hyperpolyglots’ include Alex Rawlings, Luca Lampariello, Moses McCormick and Tim Doner. With 11+ languages Luca Lampariello is an inspiring example of a ‘hyperpolyglot’

So what about people who learn to speak an incredible number of languages?

There is an exclusive level that few language learners achieve. While the 11+ of ‘hyperpolyglottism’ set by Erard is a big milestone for language learners, some polyglots go significantly further. That said it is relatively rare for even top language learners to speak 20+ languages so a new benchmark for this level should be the highest accolade. This new category is ‘ultrapolyglottism’, a level above ‘hyperpolyglottism’. The languages should come from a minimum of 5 language family branches in the ‘ultrapolyglottism’ category. A high competency in so many languages is very difficult to maintain as one´s time to use or learn the languages is spread out over more and more languages. Examples of these rare ultrapolyglots could be Richard Simcott, Alexander Arguelles, Emanuele Marini and Ioannis Ikonomou.

UK ultrapolyglot Richard Simcott is a founding father for YouTube polyglots

The level to which historical figures such as Mezzofanti and Krebs spoke their amazing number of languages is sadly impossible to verify today. Maintaining such a huge number of languages to such a high level is an almost superhuman feat. 20 languages is around the upper limit for what has been demonstrated on video by YouTube polyglots in the last few years since they started uploading their videos. Verifying their levels in each language would be vital in ascertaining where the upper limits in language learning lie at this point in time.

Conclusion

The level to which historical figures such as Mezzofanti and Krebs spoke their amazing number of languages is sadly impossible to verify today. Maintaining such a huge number of languages to such a high level is an almost superhuman feat. 20 languages is around the upper limit for what has been demonstrated on video by YouTube polyglots in the last few years since they started uploading their videos. Verifying their levels in each language would be vital in ascertaining where the upper limits in language learning lie at this point in time.

Update Following the constructive feedback received from other polyglots and those interested in the topic, I have revised the article (as was intended by the intersubjective nature of the debate). Main changes: 1. Addition of minimum language family branches in the categories. 2. Leaving ‘hyperpolyglot’ at 11+ languages as per Erard’s classification (as to avoid confusion).

Featured Image: Benny Lewis – Superpolyglot, author of ‘Fluent in 3 Months’ and one of National Geographic’s Travelers of the Year 2013

Michael has been an avid language learner and traveler for many years. His goal with LanguageTsar is to discover the most fun and effective ways to learn a language. He is currently learning Japanese, French and Indonesian.

Comments are closed.